Not Fade Away

There is a phenomenon I noticed early on in my meanders in the canyons of this land…that petroglyph and pictograph sites are surrounded by gardens of medicinal and edible plants. Not only does this speak to intentional cultivating of these plants by indigenous peoples but also says something about the spirit that still dwells in these places.

Recently I encountered one of these gardens growing at the entry to a very long and deep alcove nestled into red rock. On the back wall of the alcove there are several pictograph figures, that appeared to be shamans, slowly fading where the white clay is washing away or rock is flaking off of the wall. There is something I feel upon seeing these figures, something energetic that feels solid, friendly and hopeful. My story is that the figures depict a friendship between four medicine men from different clans, coming together in peace.

While I was exploring the alcove, I felt the urge to weed out the tumbleweeds that lined the pathways into the alcove and grew in the garden. While weeding I felt aligned with the women who once tended to this garden. Earlier in the day I had jumped with a start upon seeing an indigenous woman with a blue poncho wrapped around her, who then turned into a tall tree stump when I turned to face her. This happened twice while I was there and it was this woman who I envisioned as I pulled tumbleweeds from the site while day faded to dusk.

In the morning I left my camp and walked barefoot downstream towards the alcove singing a song to the ancestors of this place. Upon arriving at the garden, I gasped ...the garden was now in a full bloom of purple spiderwort in the midst of salmon orange globemallow. The spiderwort was a new development, not in bloom the day before. Bees were foraging on the blossoms and as I stood there the garden took on even more depth as a desert food “forest”.…. Indian rice grass, globemallow, spiderwort, prickly pear, pepper mustard, four winged saltbush, sumac, asclepia and several species of artemisias…all edible and medicinal plants were all glowing in the first light of the new day.

Brilliant spiderwort

This whole experience landed in my soul as what it means to be native to a place…that we care for and tend to Earth as our Home… which includes the place where we live and the greater environment. Walking this canyon with a sense of Belonging, I disentangled baling twine from debris that wraps around the cottonwood trees during flash floods. I prayed for the water and All Beings. I weeded the gardens of those who walked this land before me.

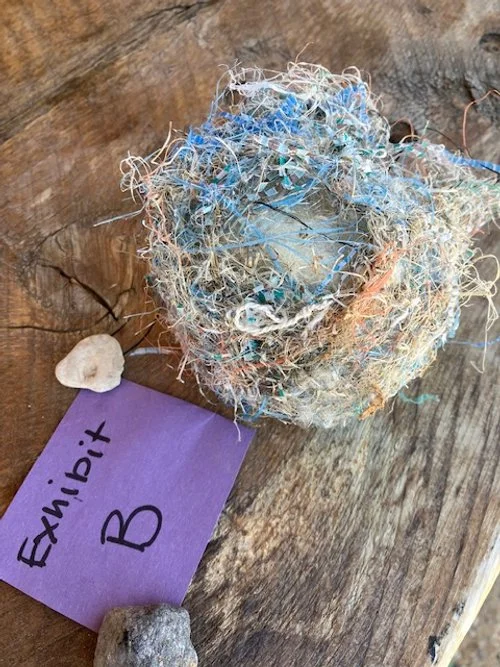

Baling twine I collected while walking in the river

An Oriole nest woven with baling twine may seem like an adaptive strategy, however the plastic twine means that this nest lacks breathability and negatively impacts baby birds

While walking in the river with thoughts about what it means to be native to a place, a memory from my childhood arose: on the corner of our street a Vietnamese man would sweep the sidewalk around his house every morning. Seeing how he cared for his place, regardless of being from another country, must have impacted me deeply to be with me decades later.

What if each of us cared for our place as if we were native to where we live? As if we belong here?

“Connection to place is just one breath away.”

When we open our awareness to the place where we live, we begin to notice that our place has other inhabitants…birds, animals, trees, insects, plants…and then we notice that our actions have an impact on them. In recognizing this we care for our place beyond our personal needs.

This could be as simple as putting out a bird bath, or planting a bed of wildflowers for the pollinators while refraining from using pesticides and herbicides, to allow for the natural balance of insects. Or turning out unnecessary lights at night to benefit the nocturnal creatures, as well as birds and plants (and soon you’ll discover that you benefit as well).

What is one new action that you can do to care for the place where you live? What would it feel like to live as if you are a good ancestor, leaving behind a place who is well cared for, for future generations of humans and the greater community of All Beings?

Let’s not just fade away.

It was hard to frame the whole garden at the alcove so here is another site with globe mallow

River Bees

guest written by Zach Carlsen

In December of 2023, I applied for a grant called Lawns to Legumes to turn my in-town lawn 100% into a pollinator habitat. Recently, Constance asked me, “Why?” This is my response:

It was morning. I watched the rabbits from my sunroom. The squirrels were already chasing each other—kinetic, creative, efficient in their movements. 30 feet high, their matrix. Dazzled by their use of the X, Y, and Z axis of the black walnuts’ canopies. Their play, somehow both nonchalant and caffeinated. As always, I was amused by how they run headfirst down the trunks. The carpenter bees blending in with the shadows of the lilies. In between all that: the woodpecker, the robins, the little yellow songbirds, and the cardinals. We were, in that moment, all starting the day together.

I stood for another ten minutes watching, not thinking but also not not thinking—for me, the very definition of mindfulness—and I realized for the first time: I know these animals. I see them everyday. And they see me. They’re not just any rabbits, songbirds, and squirrels—they’re specifically these rabbits, songbirds, and squirrels. They’re the same ones from yesterday, and last week, and last year. They’re not some generic part of the landscape. They are a part of my intimate network of familiars on this planet. With no more pretext than that, I began to cry, grateful for them.

I live in a sleepy Minnesota rivertown on the western bank of the St. Croix. Once known for logging, Stillwater is known these days for its antique shops, historic riverboats, and our annual Lumberjack Days Festival that once hosted Lynyrd Skynyrd. I’d never heard any mention of the bunnies or bees in the tourism brochures, but suddenly, that morning, I wished someone would.

I moved closer to the window. Each of these animals has an identity, with preferences beyond what one might call instinct, and my yard is where that uniqueness plays out. One bunny likes the clover by the garage, the other likes it by the coiled-up hose (and, look! that second one notices the Monarch as it floats by.) One squirrel grazes the perimeter of my compost pile, the other all but swims in it. For many of them, my property is their entire physical world. I suddenly felt the responsibility that had been there all along.

Stepping outside, I easily counted a dozen different kinds of insects in 11 square inches of grass—non-native, Kentucky bluegrass, sod you can buy in a roll and flap down like a living throw rug. It made me wonder, what kind of life could flourish with a more native groundcover? How could I make life a little better for those who live outside 100% of the time? Afterall, I am more on their land than they are on mine.

Anywhere in my house, when I am home, I am never more than 100 feet from one or many of them. In terms of hours-spent-in-proximity, these animals are the closest beings in my life. And, while watching the bunnies’ incredible intelligence and precision—this tiny plant, not that one, this tufted flower today, that one tomorrow once it grows a little more—it occurred to me that they might live out their entire bloodline on my little lawn. How many of their babies have been born under my porch? Why did the robin choose my downspout to make her nest?

I tend to like things that are hardcore—not necessarily extreme, rather, things that have an all-in attitude—committed, fully sent. As far as I know, none of these animals or insects migrate. Each species has cultivated a unique strategy to outlast the winter, which commonly holds stretches of -10 to -30 degree days. What could be more hardcore than that? They endure harsh conditions for months in order to stay here. Not somewhere else, not up the street, not across the river. Here.

The animals living on the tiny lot that I own are all-in on this land, year-round, year after year. But, am I? Most don’t travel far. If my lawn is their physical world, my block is their universe. What I do on my quarter acre trickles over to my neighbors on each side, too. I can help improve conditions for all of them—for the bunnies who chose their backyard over mine, for the squirrels who chose their maples to nest in, for the lady down the street who gifts her lilacs to the driver of the eldercare bus. If I see more bees and butterflies, we all see more bees and butterflies. And, for now, that’s why.

More Info Contact Zach@ZachCarlsen.com